Apparatus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

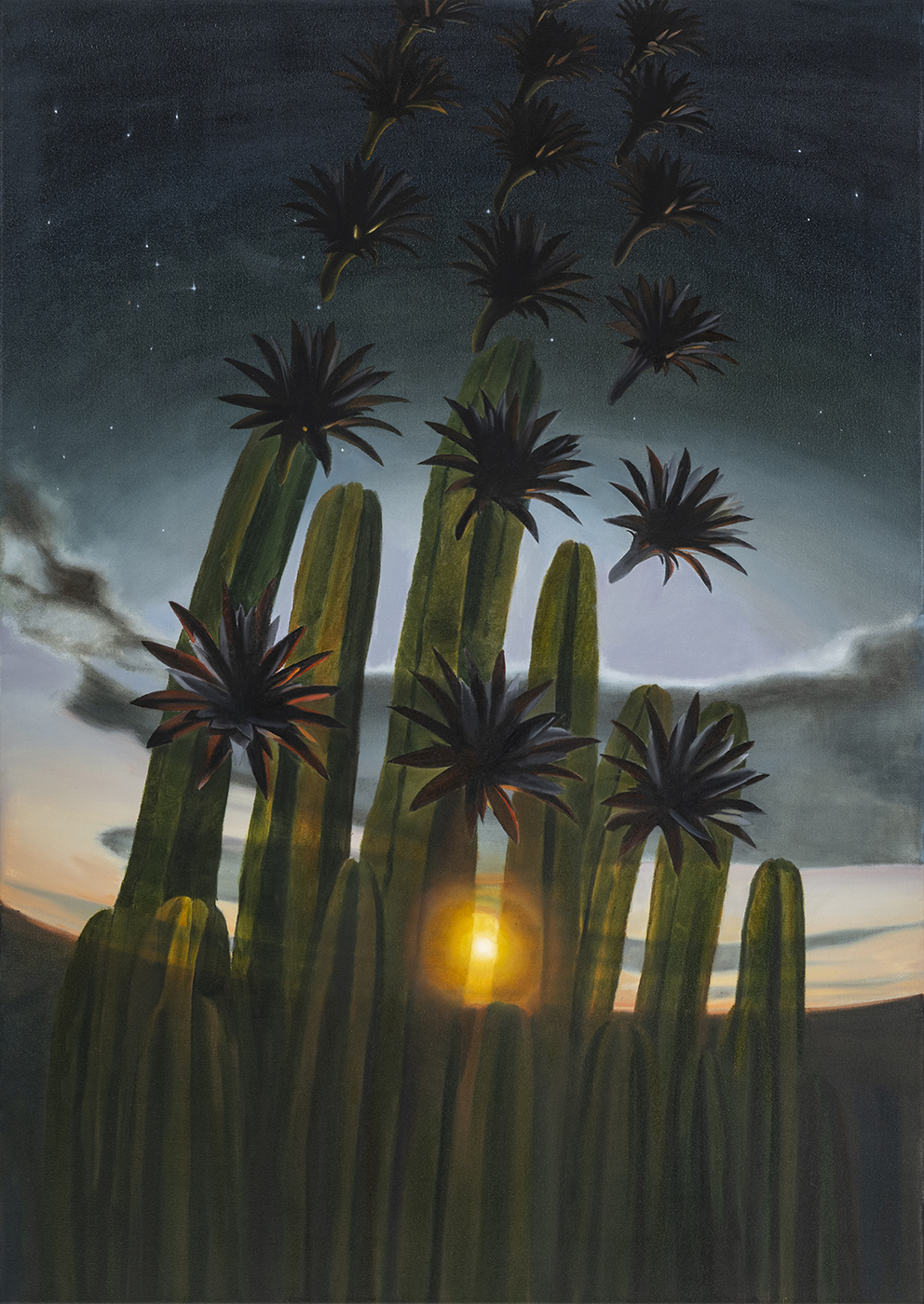

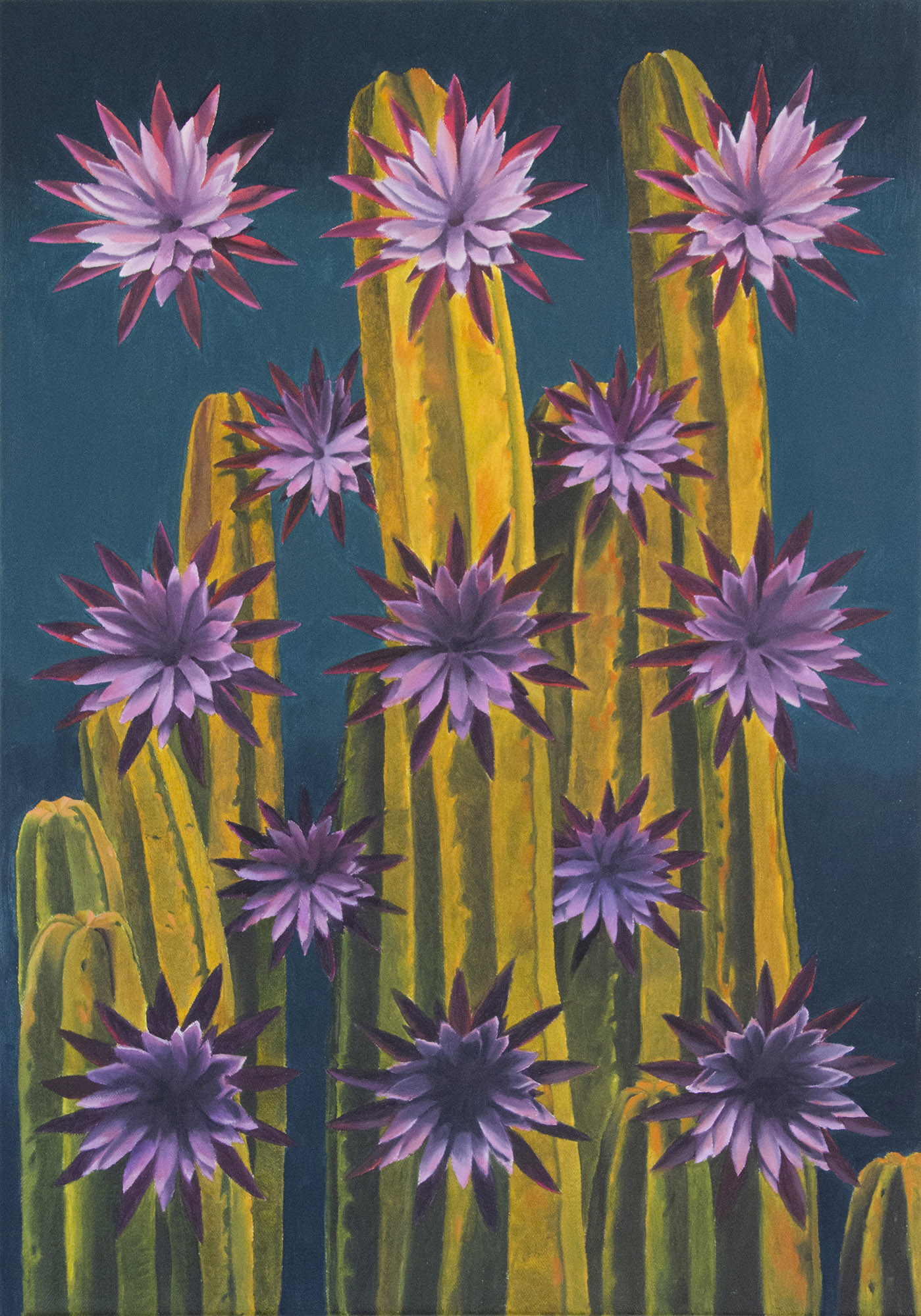

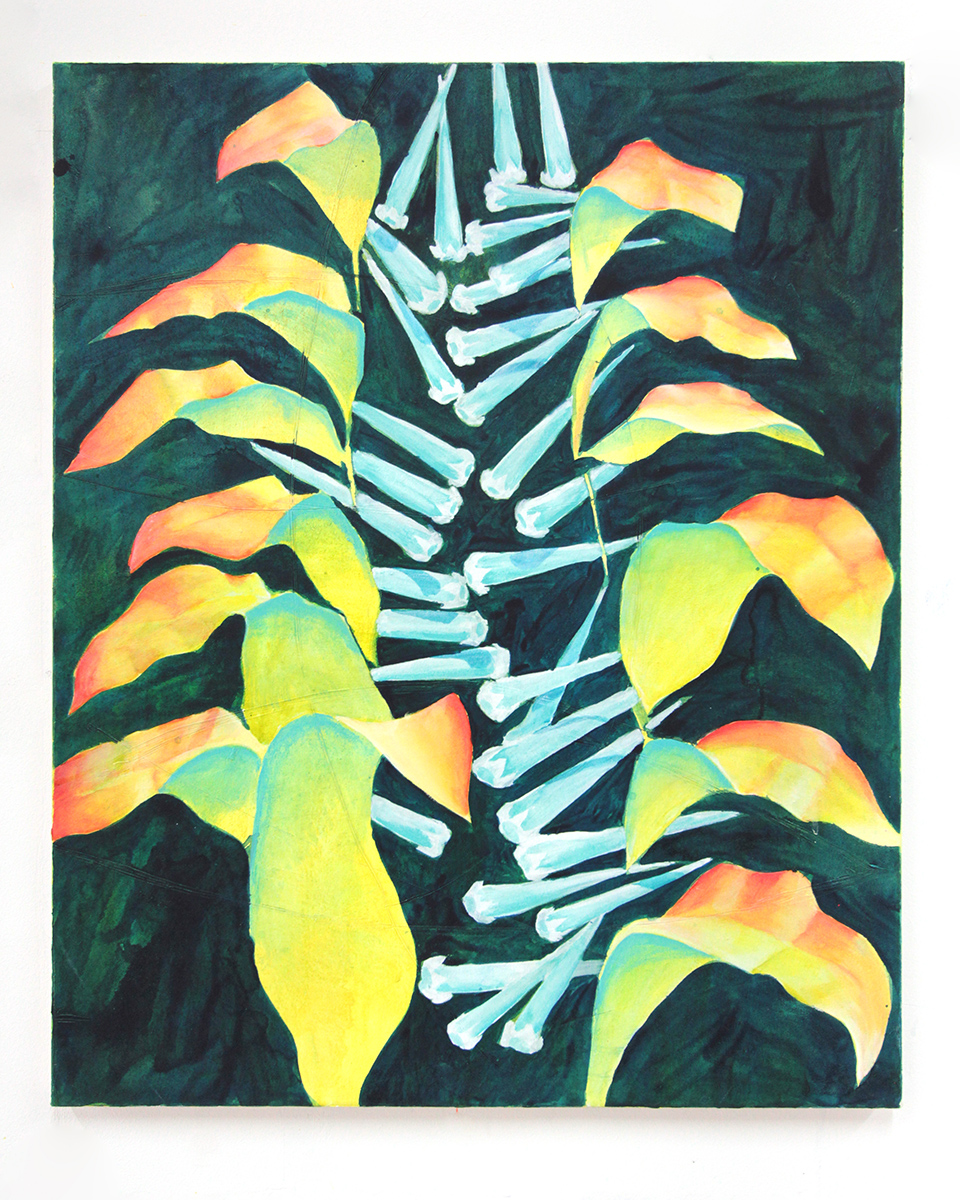

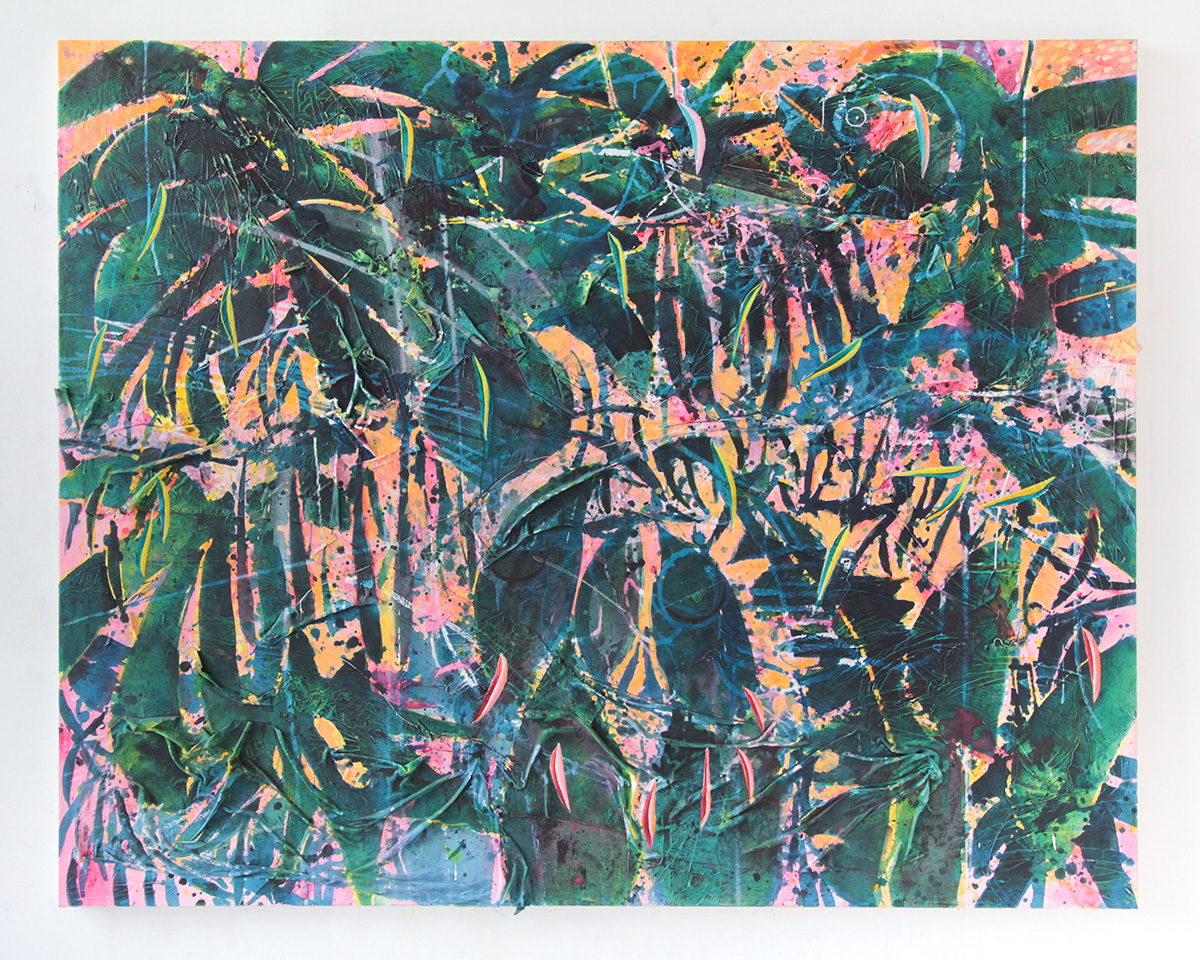

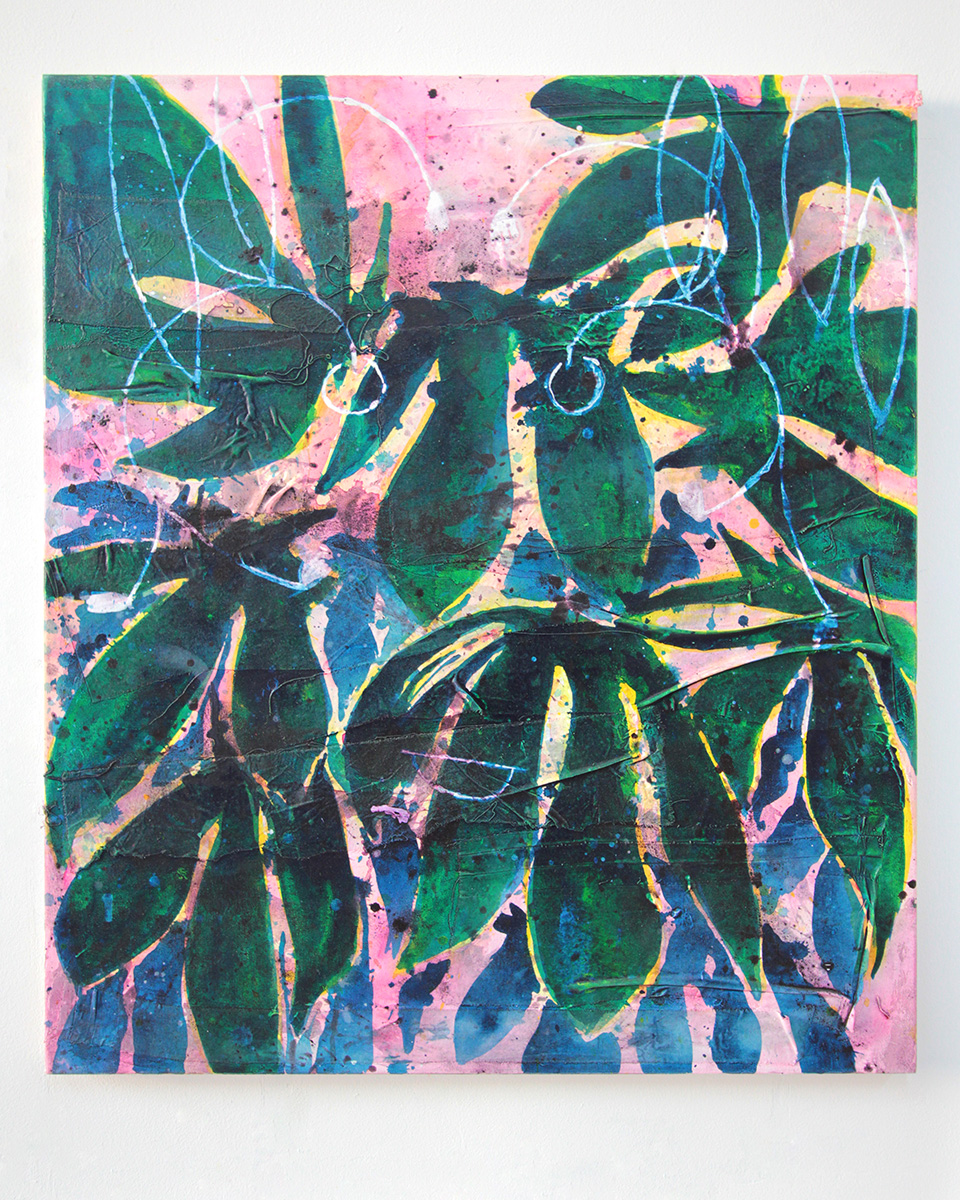

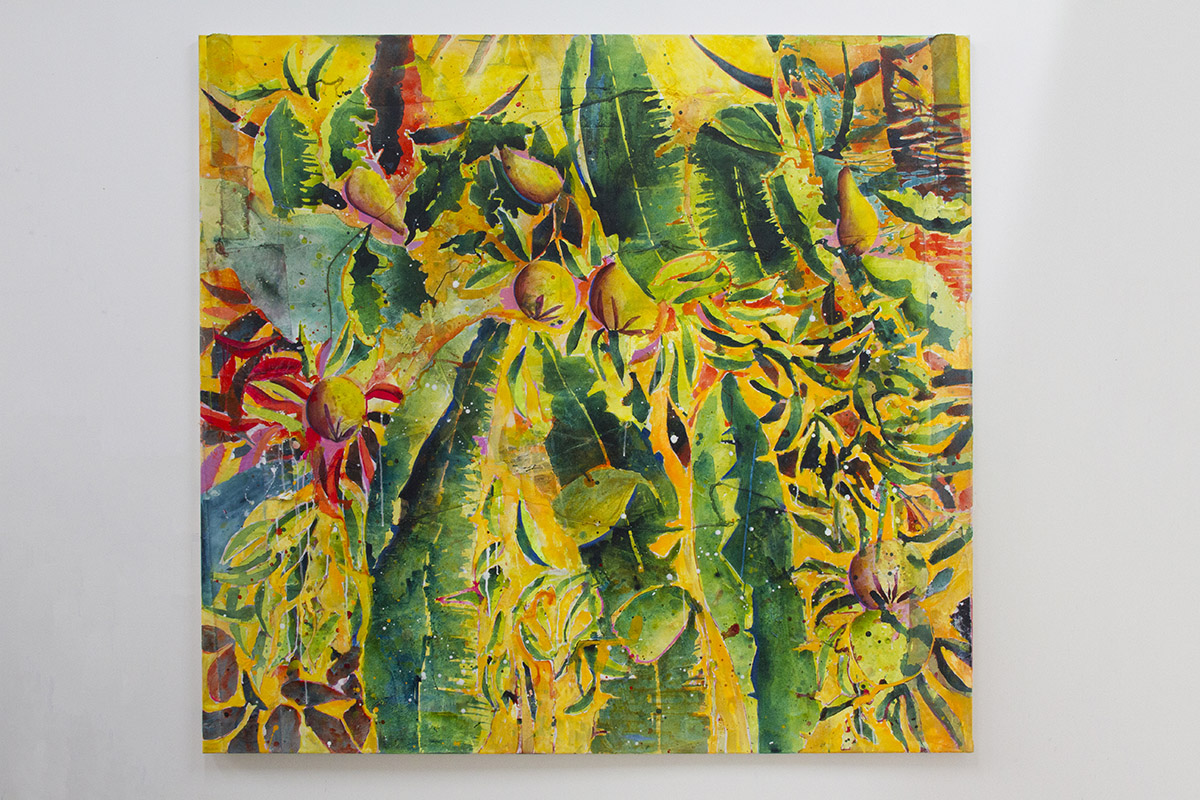

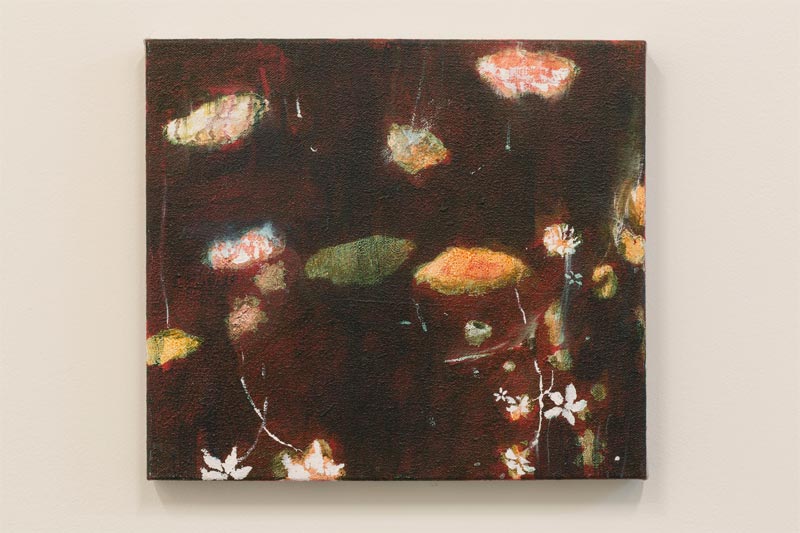

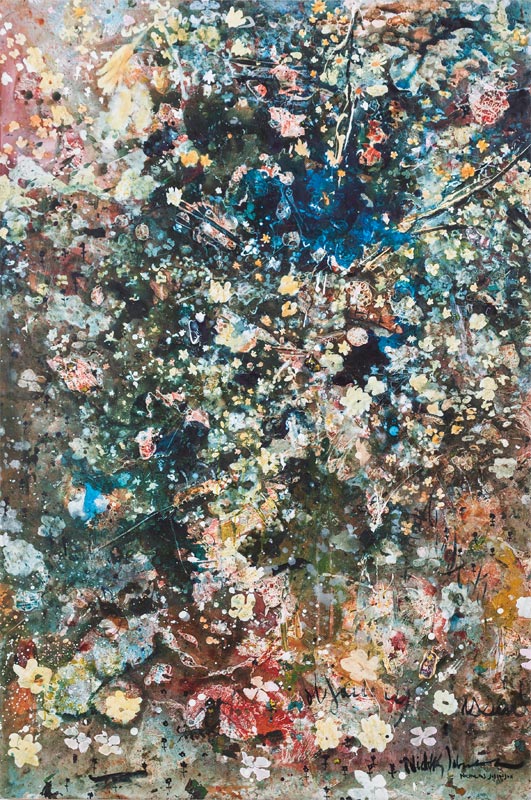

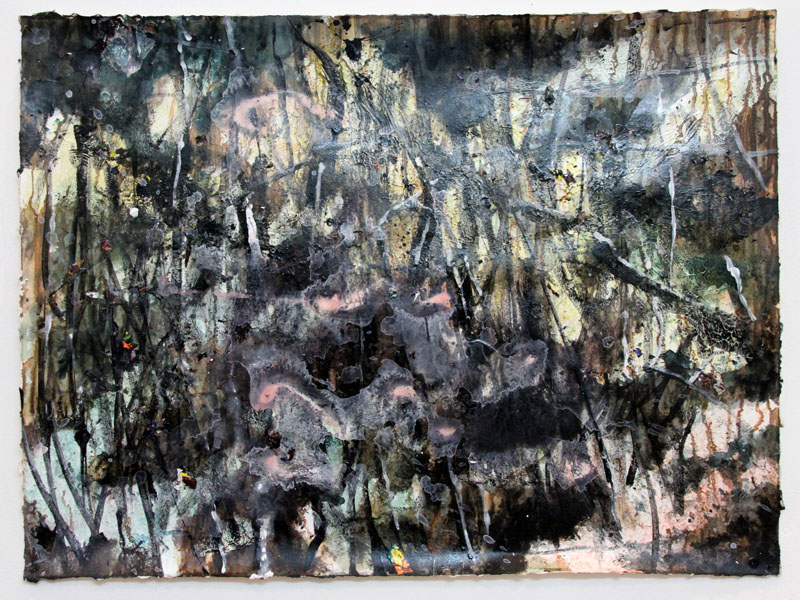

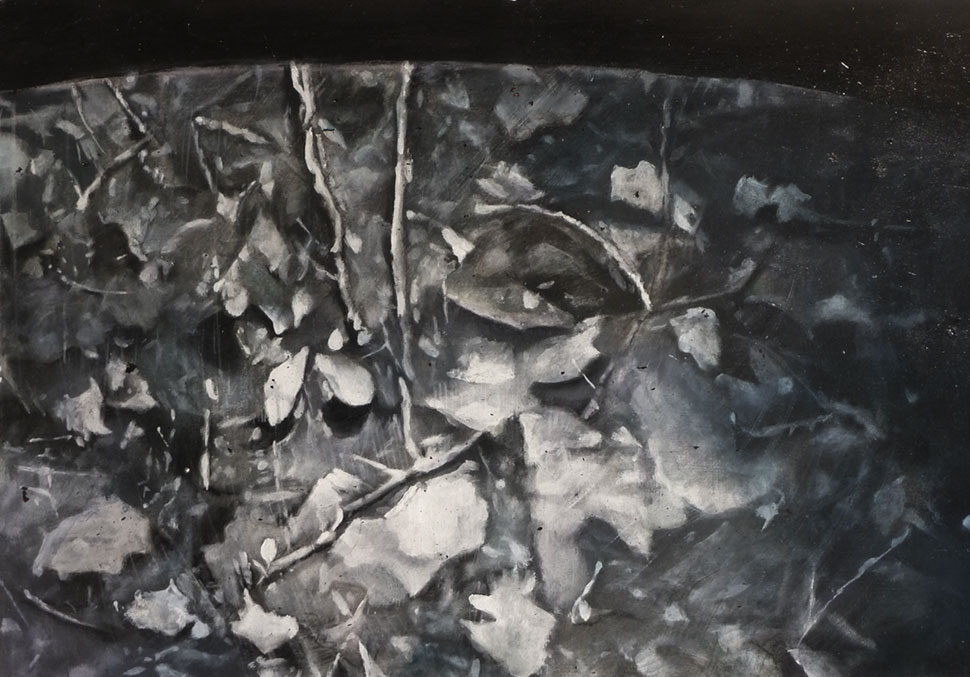

The exhibition comprises oil paintings and animations on CRT monitors of submerged and suspended landscapes populated with arrays of digitally modelled botanical forms.

Virtual suns illuminate these scenes as their images are refracted and reflected in obsidian mirrors.

Three tools of reality creation—that conjure or reveal worlds beyond our grasp—convene in this work: painting, optics, and psychotropic plants.

Each such apparatus extends and limns the contours of a reality that we can perceive.

Exhibition Text, Alex Meurice, 2022:

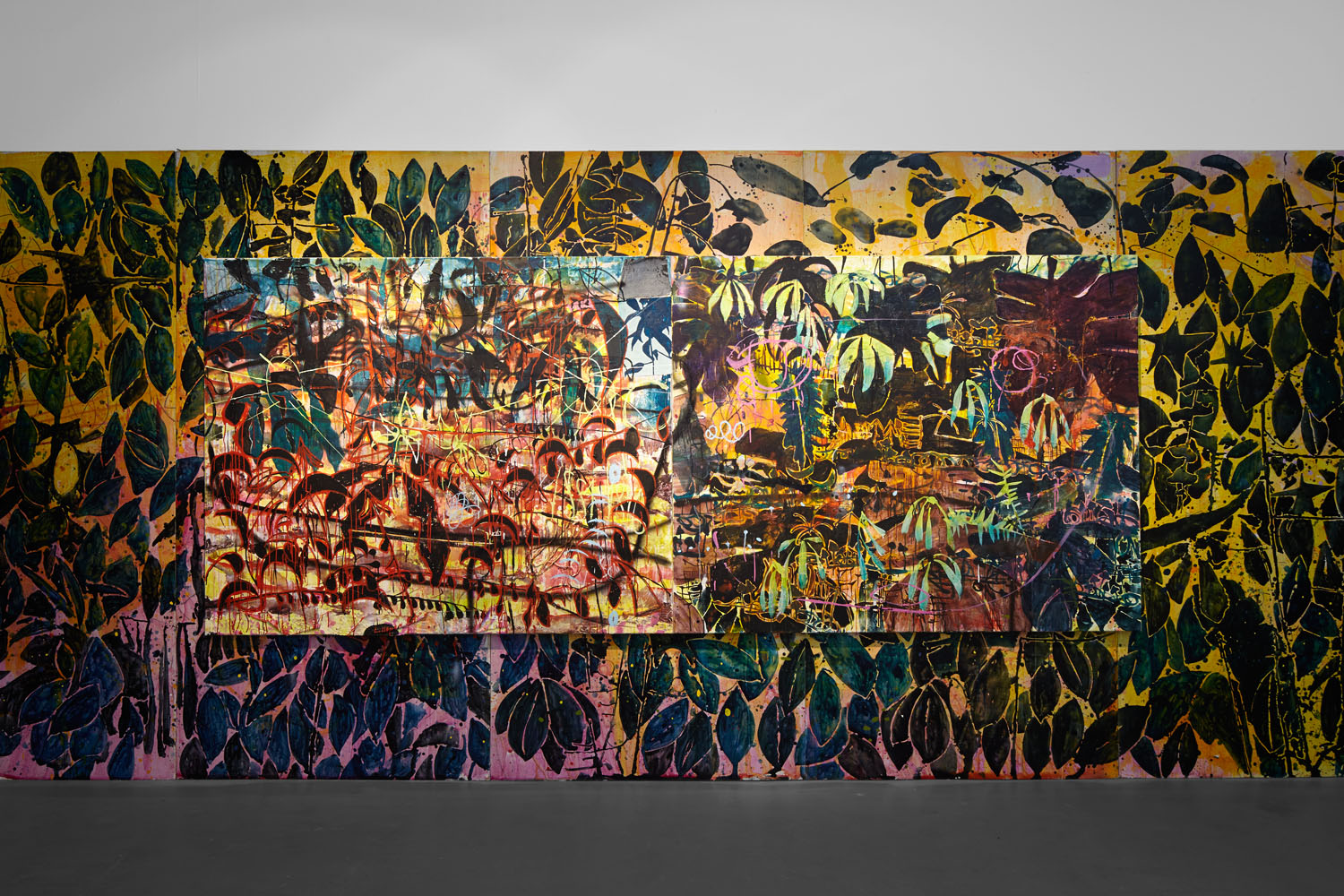

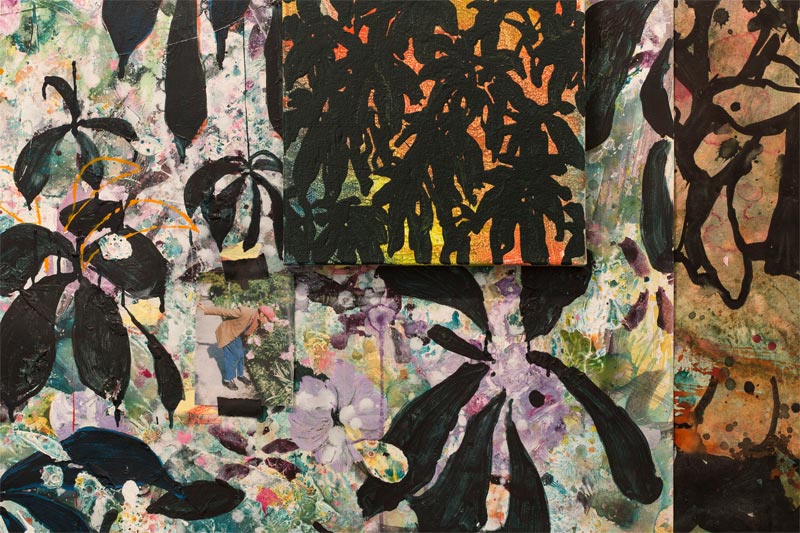

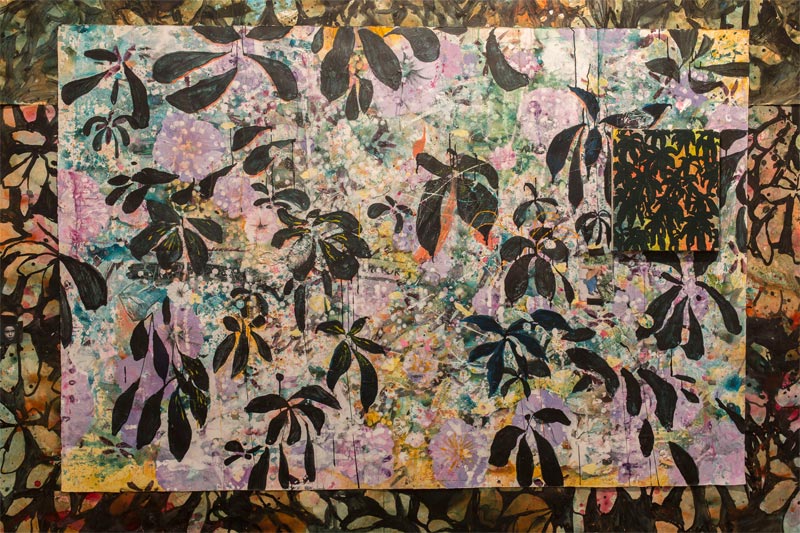

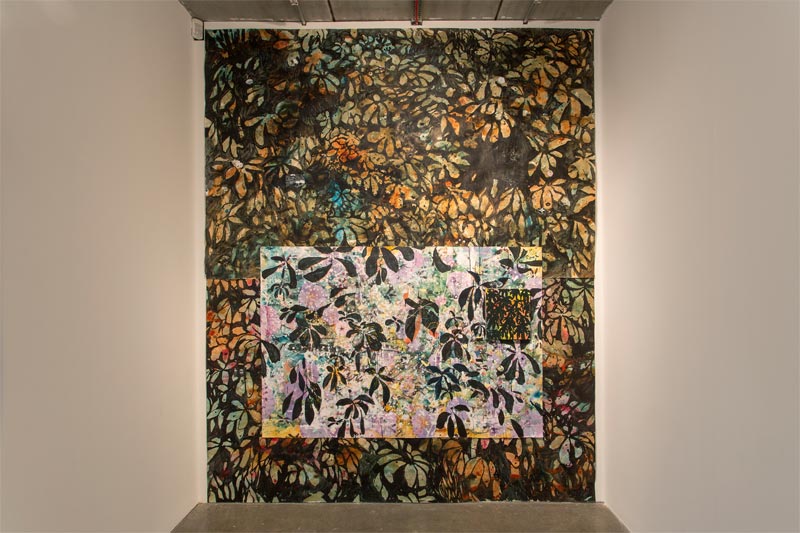

Foreign & Domestic is pleased to present Apparatus, Nicholas William Johnson’s first solo exhibition in New York. The exhibition combines oil paintings with digital animations on cathode-ray-tube monitors which appear out of a parallel virtual space. Johnson fashions specific botanical forms and arranges them into structured compositions within his simulated worlds: digital dioramas populated with psychotropic flora in liquid or gaseous suspension. These scenes are artificially illuminated and reflected in convex obsidian mirrors. The dark glassy curvature of the mirrors refracts, scatters and distorts the virtual light, subdues tonal values, and imparts an otherworldly gloss to the rendered image.

With Apparatus, Nicholas W Johnson extends his scholarly enquiry and painting practice to create an exhibition that weaves together disparate traditions of world creation – or apparatuses: painting, psychotropic plants and optical technologies. Through his work Johnson asks complex questions about the structure of representation, perception and meaning, as technology continues to blur and distend the boundaries between art and life, matter and simulation.

The word apparatus shares deep roots with the word ‘appear’: ad-parare, or to-make-ready. ‘Apparatus’ suggests the tools, equipment or systems for preparing and allowing something to appear, for rendering a part of the world visible. The word also suggests obedience and submission: an ideological apparatus, a state apparatus, the apparatus of justice. An apparatus can be bureaucratic or divine, used to control or to liberate.

Obsidian – a blade at the junction of worlds – was such an apparatus for Mesoamerican civilizations. ‘Smoking mirrors’ of finely polished black volcanic glass were used to peer into the future. Just as sound can reflect off a surface and echo back with a delay, so in dark mirrors images appear to have travelled from another time or place. The reflected image appears simultaneously behind the mirror’s surface and behind the viewer, eluding touch behind an impermeable membrane. Obsidian mirrors were closely associated with water and the underworld.

John Dee, the court magician of Elizabeth I, famously owned an obsidian mirror smuggled from a recently colonized Mexico, which he called his ‘shewstone’, and others called the ‘Devil’s lookingglass’. Dee used his mirror to communicate with angels and the spirits of the dead, making sure to carefully stage the show-stone by a window, in natural light, before questioning the angels on natural science or hidden treasure. Dee’s theatrical setup resonates with Johnson’s meticulous staging of forms, lights and angles in the digital modelling environment.

Many of the plants depicted in Apparatus possess psychotropic qualities. The ingestion of mind-altering plants in a ritual setting inscribes altered states of consciousness into the participants’ bodies, like a painter’s reification of otherworldly images – mediated by optical technologies – is inscribed onto canvas. Johnson’s images glide between phase states – from glossy solids through liquid oils and digital gases – they remind us that all vision is augmented, and that no pure perception exists that precedes its apparatus. Nature is always already technology, and technology itself expresses culture.

The ritual use of psychotropic plants for mediating and constructing worlds has been an important apparatus in many cultures, and has long been suppressed in the name of modern science and religion. Likewise, plants and their image are a contested site for anxieties towards nature, gender, race and the other. In our efforts to control and categorize plants we graft on a part of ourselves: plants bear witness to the violent processes of evolution and history, and possess an archival knowledge that can be transmitted to and interpreted by other sentient beings.

Four viewing terminals are installed on plinths around the gallery floor. Each monitor screens digital animations on two minute loops. The digital suns rise, fall and circle around, generating dynamic lighting effects in the obsidian mirrors. The cathode-ray-tube monitors project an anachronistic quality, with their dark convex glass and images produced by electrons colliding with a phosphorescent screen, crackling with static, to display the latest generation of digital animation. One viewing terminal screens an animation of the gallery itself, flooded with murky green water and rippling lily stems, artificially illuminated from the street, an upside-down homolog of the exhibition space which evokes the forgotten zones of a video game.

Johnson’s ongoing project of illustrated encyclopedia – “with idiosyncratic entries on the history and culture of botany and botanical illustration, the language, science, symbolism, folklore and occult beliefs surrounding and associated with flowers and trees” – is represented here with a selected library of the artist’s publications and commissioned texts from the past decade.

Apparatus is an exhibition about the creation of meaning, the encoding of information, and the devices used for imaging and constructing reality. By bringing together painting, optics and psychotropics, Nicholas William Johnson conjures a series of connected but distinct worlds, dreamscape vignettes for staging ‘real objects of the mind’. In order to produce meaning, an apparatus must pair with a social ritual, or scaffold: painting with exhibition making, lenses with the scientific method, psychotropic plants with ceremony, dance and music. Apparatus proposes that the devices which frame reality do more than passively record phenomena; an apparatus reveals a set of limits within which new meanings become possible; divination becomes conjuration. The art of Nicholas William Johnson is such a transitional space to test, mingle and sublimate each apparatus into new world-producing configurations.

Rapture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Occami. 2022. Digital video. 10s loop. Minted as an NFT on the Ethereum blockchain via Foundation.app

The following text was written by Aliya Say (2022) to accompany the exhibition Rapture.

***

In the faraway future, that is already here, a sound could be heard. At first, it is distant, almost imperceptible. It approaches slowly, descending from high above, where sagacious noctilucent clouds veil the atmosphere tenderly. Gradually, the sound grows in strength, alternating between a low-pitched ring and a hum, until forming a giant tide, whose crystalline sonorities roll confidently towards Earth. The waves come in a repeating syncopated rhythm without crushing into, but delicately reinforcing one another. As they reach the surface of the planet, they gently envelop the enormous coniferous forest in what was used to be called Sierra Juárez in the state of Oaxaca, swishing through the muffled rustling of rotting leaves and sprouting branches with their long sustained breath-like tunes fading in and out, in and out.

The forest hushes, bewildered. Never has Planet Earth, in its 4.6 billion years of existence, heard a sound like that – it is, quite literally, otherworldly.

***

Empty of human presence for over 30,000 years, Planet Earth is overflowing with lush greenery and rapturous blooms, as it finally lives up to its Edenic promise. Gaia is stunningly beautiful – even if no satellite captures her glorious image from outer space, so she can catch a glimpse of herself in the mirror of interstellar photography. The song of the kingdom come is sweet and mellifluous, perhaps overly so – evidently missing a few chords of human presence for a truly well-pitched multispecies polyphony (who would’ve thought!).

Humans would not have recognized many of the creatures now populating their former home: while certain floral and dendritic shapes would look familiar, others would stand out as completely extraordinary and baffling. As flora learned to adapt to new climatic conditions, new morphologies have flourished: triangular leaves, dark green on one side and almost totally white on the other, so a plant could curl its foliage at the hottest time of the day to prevent overheating and uncurl on cloudy days, to conserve heat and prevent severe temperature fluctuations. Petals forming pipes, to direct excess water away from the tender pistils. Tendrils that dance their way towards ever-new heights in the crowded forest. Flowers arranged along non-Euclidean grids.

Colours, too, have transformed. Under the influence of increased radiation and extreme temperatures, new fluorescent hues have blossomed, shiny and translucent, polychromic and abysmal, enigmatic like Holbein’s azurite mixing and sampling moonshine reflected off butterflies’ wings and the light absorbed by the impenetrable depths of the Mariana trench.

***

The sound arrived, announcing its extra-terrestrial presence with a hyperdimensional embrace. Oh, the long-awaited cosmic advent! How humans longed for you, how they feared. The Other did not announce themselves in any other way than the outlandish hum. They were by no means immaterial, but they had no visible body, no form one could see and touch – only hear and perceive. Devoid of spatial extension, their consciousness extended in all directions, travelling as multidimensional waves, according to laws unbeknownst to human science even at the height of the age of quantum and cosmological discoveries. Albeit some scientists, those of a particularly mystical inclination, did know: they intuited the seemingly impossible astrophysical phenomena, but could not prove or demonstrate them empirically. Humans thus left, having their half-baked mathematical equations unresolved, and their greatest theoretical intuitions untranslated into the language of science. While they captured the cosmic microwave background, the radiation from distant galaxies all the way back from the time the universe was born, they could not decipher that some of this radiation was music. And some of it was God.

The Other arrived from the Occam Galaxy, and were thus called Occami. Not one, not many, but multiplicity itself, their sonorous body extending through the curvatures of space-time, running along the edges of deflections and black holes. They did not pose a threat to Earth’s nonhuman inhabitants or to the planet itself ¬– but they did have a purpose, one they needed to communicate to Gaia gently, yet resolutely. Occami, who travelled for aeons before reaching the solar system, knew they were too late to meet the human race, but they revelled in singing their prayerful undulating song to the myriads of vegetal beings. They exchanged their astral tune joyously with the flowers of the deserts and lilies of the valleys, with perennial vines and feathery mosses, with all the house plants and all the monocultures set free and re-united once again with their multispecies sisters 30,000 years ago.

At first, the Gaian flora gave off a signal of alarm when sensing the Occami approaching, but the fears were soon relieved, poisonous spikes hidden away, tender leaves unfurled, giving way to a full welcome and a resonant embrace. The Occami did not come to colonise, they came searching for a precious gift, the story of which their long-gone ancestors have passed on to them (while Occami were capable of travelling through space-time, they did not live forever).

Occami knew of special plants that human shamans used in the ancient ceremonies: on full moon, a medicine man ingested herbs specially selected for their healing, consciousness-expanding properties. As the plant entered the body, the healer merged with and thus became the plant. In a state of vegetal immanence, the most magnificent shamans would build a verdant cosmic ladder to travel far and beyond, sometimes as far as Occam. Some of them have stayed out there and gave birth to a race of selfless super-conscious sonorous beings. Many light years later, children of Occam have come back to reunite with their vegetal mothers.

In gratitude for reunion with the sacred plants, the Occami offered their grand, transcendent, incantatory song, an eternity-long slide into blissful deliquescence, an ecstatic dissolution in all there is. Their offering to Gaia was the gift of divine music – the gift of themselves.

They Regard Us As We Regard Them . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

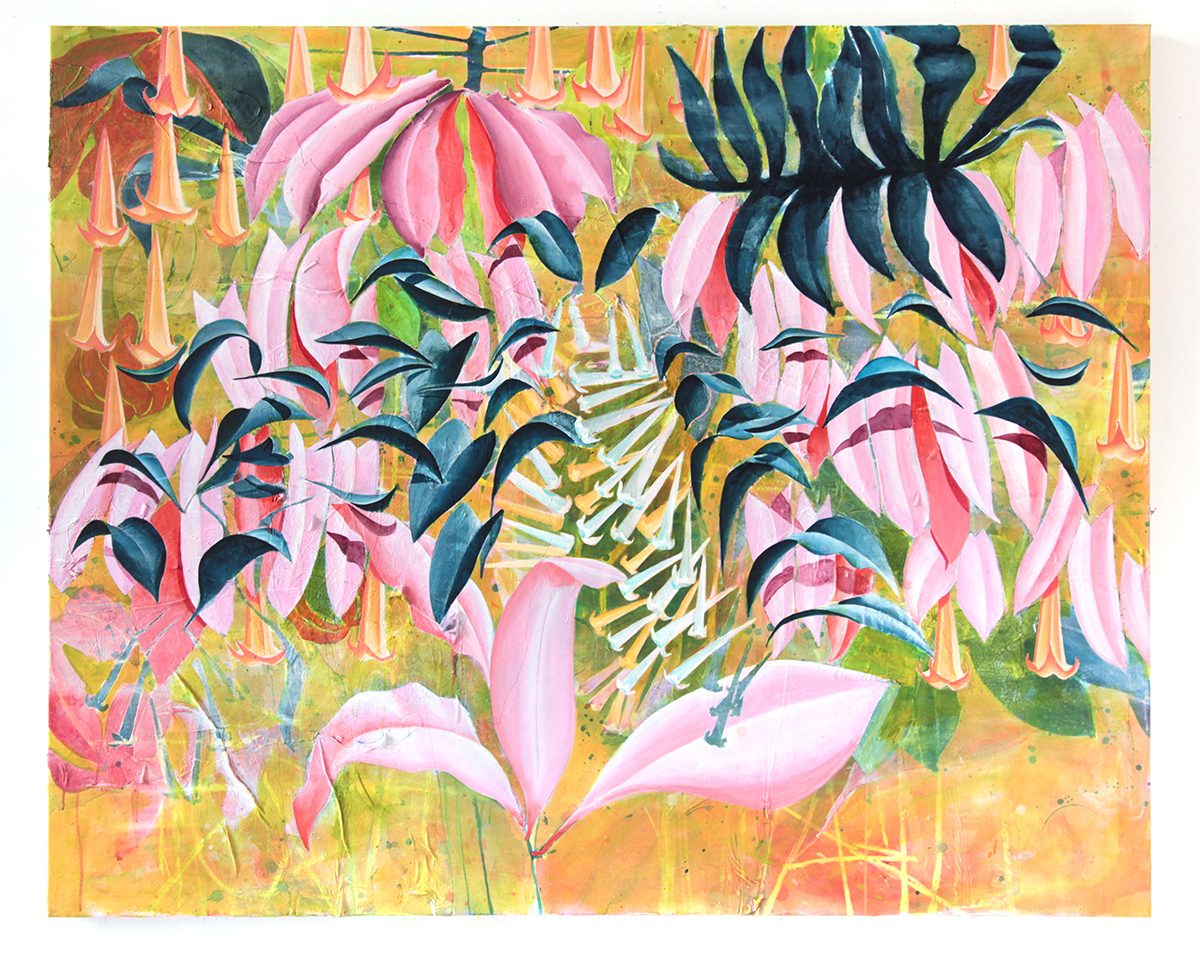

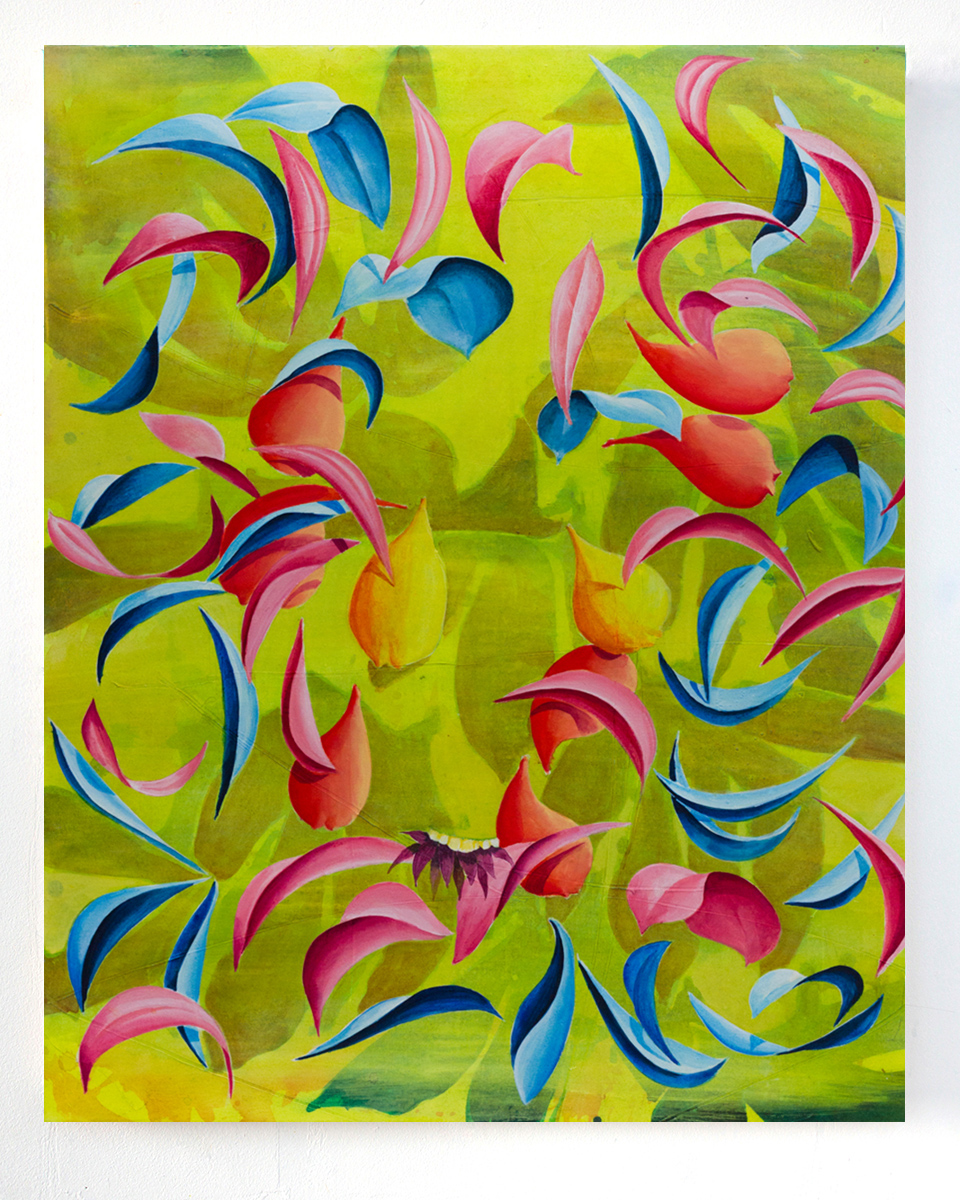

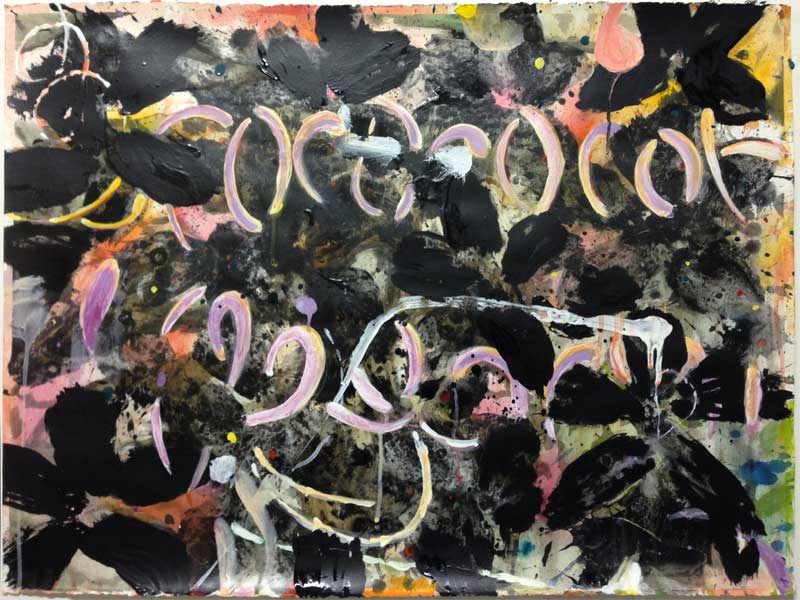

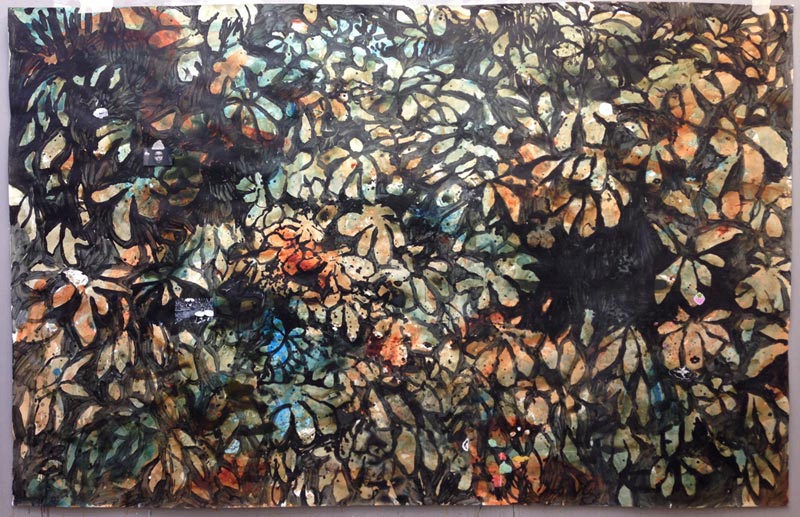

The botanist Francis Hallé observes that, ‘plants elaborate themselves according to strict rules, rules that lead to the conceptualisation of models’. The dynamics of these models and their further implications are investigated in Nicholas William Johnson’s new paintings. In his works these rules are altered – flowers bloom in digital arrays, fruits and leaves are suspended in double helices. Johnson renders plants – other lifeforms – as dynamic, interactive systems, examining our often-unquestioned belief in the passivity of nature. Repetition of botanical forms in futuristic digital arrays confers the idea that they constitute systems of information. Plants and trees are systems that reiterate, recursive nestings of individual elements, to form an interconnected colonial system.

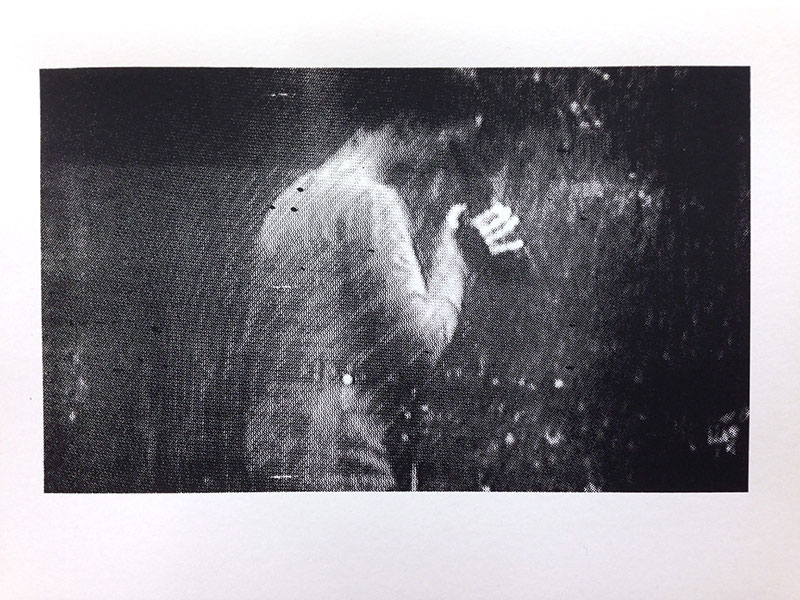

As part of this new body of work Johnson has produced a short film on Super 8 adapted from James Lovelock’s last book Novacene. In the truest sense of the term Lovelock has written a science-fiction that proposes humans will create a hyper intelligence that will design itself as a self-reproducing networked atmosphere of electronic life. Lovelock proposes that this ‘system’ will work in concert with humans to restore ecological balance to the planet. This vastly superior intelligence will exist on a temporal plane of awareness very different from our own. It will come to regard us as we regard plants, life existing on a much slower temporal and earlier evolutionary scale. Just as plants are also aware of us and other animal life and interact with it – contemporary science is beginning to articulate how – in turn we will be aware of this hyper-intelligence and interact with it. Johnson’s film explores the idea that we may only come to fully understand nature and ecology through the creation of networked technologies, an anachronistic futurism. Other life through a post-anthropocentric lens, is not individualistic but vast, lively, complex networks of interconnected and recursive points of awareness.

Further ideas in Johnson’s film that this electronic life can manipulate DNA, or that genomes are saved and re-printed in altered forms for example, are adapted from Octavia Butler’s novel Dawn. A similar science-fiction narrative underpins Johnson’s paintings, plants whose code and patterns of self-replication have been altered, pose the question what is life and awareness if it is different from what we know and accept to be ‘correct’.

We must consider other forms of life and renew our vision of life. Consciousness, perception, awareness, do not begin and end with human perceptual mechanics. Other forms exist. Ecological crisis has motivated a turn in critical thinking, a non-human turn. The sublime hyperobjects articulated by Timothy Morton are systems and networks so large they evade total comprehension. Michael Marder’s phenomenological framework of plant intelligence. Jane Bennet says, ‘the nonhuman turn can be understood as a continuation of earlier attempts to depict a world populated, not by active subjects and passive objects but by lively and essentially interactive materials, by bodies human and nonhuman’.

For his film, Johnson has commissioned new music from the experimental Belgian band Razen, who have produced an extra track to their 2020 release Robot Brujo that soundtracks the film.

Plant Communication Network . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Inns of Molten Blue. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Dewdrinker . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Averard Hotel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

City and Guilds Residency 2015 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

And The Bush Said Nothing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A Punk Smelling Flowers at the End of His Life . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2013 – 2014 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2011 – 2012 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Oak Trees Lullingstone Park . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

(2012 – Ongoing)

In the 1820s Palmer lived in a self-imposed rural exile in the town of Shoreham, Kent. Palmer would walk the whole to reach Shoreham from the Old Kent Road in south London. Palmer was an autodidact and his weird, visionary, borderline psychedelic images from this period were at odds with aesthetic sensibilities of the time. A series of large watercolour and ink drawings from this period depict the ancient oak trees of Lullingstone Park in Shoreham. Some of these trees still stand today, and one in particular bears a striking resemblance to a tree from Palmer’s suite of drawings. Since the summer of 2012 I have been making frequent trips to the park and filming these trees. The films are all made on Super 8mm, old technologies seem to suit.

Rose Branch Minuet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

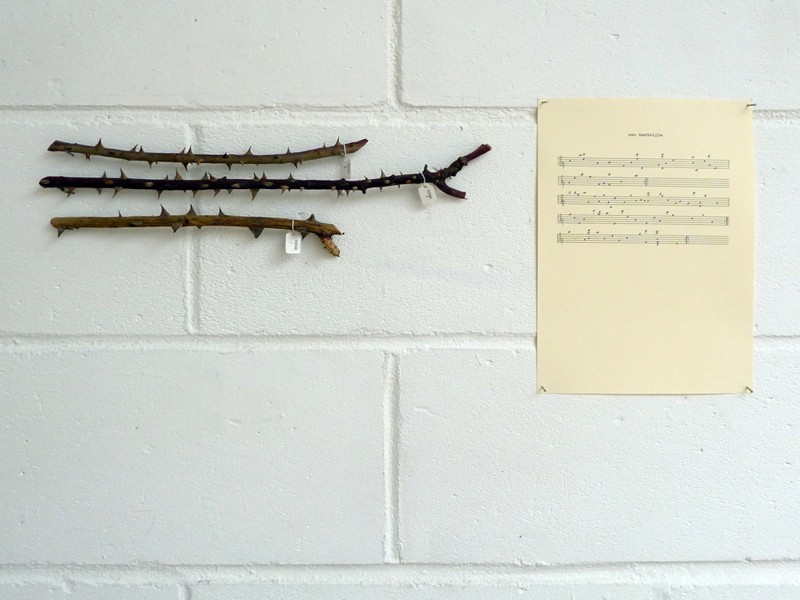

Rose branches from a January pruning were cut to a manageable size and brought to the studio. Laid out on the table I came to think that their thorns resembled notes on the staves of musical notation, or pins on the drum of a music box. Each branch was wrapped in tissue paper and the resulting pattern of pin prick holes was transposed onto a musical staff. This ‘composition’ was then carefully punched into a notecard which could be played back through a toyshop musicbox device. This was fixed to a violin which, functioning as a resonance chamber to amplify the sound, was in turn amplified and connected to an electronic delay. When the user ‘plays’ the instrument the sound continues to reverberate through the space for the length of the electronic delay.

This work is accompanied by still images from a Super 8 film of the rose bush from which the branches were cut. The stills are taken one from each second of a thirty second clip, which laid out in this way resembles a Muybridge-esque early moving picture.

(Rose branches, musical score, music box, modified violin, electronic delay, amplifier, photocopies on acetate. Dimensions variable.)

A Crazed Flowering . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Published in 2013 as an edition of 60. This 113 page document comprises the encyclopaedia A Botanical Miscellany, and the essay A Crazed Flowering. It is heavily illustrated throughout. Intended as a text to accompany exhibited work it charts a meandering path through a vast number of influences and references which inform my practice.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

An interesting study could be made of modes of decay in sci- ence fiction novels and particu- larly those of J.g. Ballard who catalogues a particularly inventive assortment: petrifaction, crystalli- sation, overgrowth, damp, drought and a number of which i’m sure have slipped my mind. From The Crystal World:

Instantly I realized that the description of the forest ‘crystalis-ing’ and ‘turning into coloured glass’ were exactly truthful. The long arc of the trees hanging over the water dripped and glittered with myriads of prisms, the trunks and fronds of the date palms sheathed by bars of livid yellow and carmine light that bled away across the surface of the water, so that the whole scene seemed to be reproduced by an over-active technicolor process. The entire length of the opposite shore glittered with this blurred chiaroscuro, the overlap- ping bands of colour increasing the density of the vegetation, so that it was impossible to see more than a few feet between the front line of trunks (Ballard 1974, 81 & Ballard 2008, 68).

‘… The likeliest reversal

of decay being petrifaction …‘ (harbison, 110).

See also The glass Flowers at harvard.

And of the effects wrought by botanical overgrowth upon the remains of abandoned civilisation John wyndham, mentioned above, elaborates below from The Day of The Triffids:

Viewed impressionistically from a distance the little town was still the same jumble of small red-roofed houses and bungalows populated mostly by a comfortably retired middle class – but it was an impression that could not last more than a few minutes. Though the tiles still showed, the walls were barely visible. The tidy gardens had vanished under an unchecked growth of green, patched in colour here and there by the descendants of carefully-cultivated flowers. Even the roads looked like strips of green carpet from this distance. When we reached them we should find that the effect of soft verdure was illusory; they would be matted with coarse, tough weeds (wyndham, 241-2).

Geoff Dyer in his book Zona (2013) – from the russian ‘zone’ – writes about the subtle magic of the damp and drippy overgrown landscape of the zone in Andrei Tarkovsky’s science fiction film Stalker (1979):

… Weeds and plants swaying in the breeze. The tangled wires of a tilted telegraph pole. The rusting remains of a car. We are in another world that is no more than this world perceived with unprecedented atten- tiveness. Landscapes like this had been seen before Tarkovsky but … their beingness had not been seen in this way (dyer, 58).

Dyer suggests that Tarkovsky has brought ‘this landscape – this way of seeing the world into exist- ence,’ (perhaps we should qualify that to Tarkovsky’s medium cinema):

… Many forms of landscape depend on a particular artist. Or writer or artistic movement to render them beautiful, to make the rest of us see what has always been there (as the romantics did for mountains … ) sagging shacks, wrecked cars and fad- ing signs … [The] ‘Quality of a new world which none of the existing arts allowed to be imagined’ (dyer, 58).

‘Tremors from the future can be felt throughout Stalker’ says dyer (74) in its foreshadowing of the 1986 disaster at Chernobyl.

After the evacuation the Zone of Exclusion was littered with the rusting remains of vehicles that had been used as part of the emergency cleanup. Plants stitched the empty roads and cracked concrete. Trees thrust through the warped floors of derelict buildings. Leaves changed shape. Vegetation clambered up the crumbling walls of abandoned homes (dyer, 75).

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

From the fifth book of Ovid’s Fasti in which the wood nymph Chloris’ nakedness attracted the first wind of spring, Zephyr. Zephyr pursued her and as she was ravished, flowers sprang from her mouth and she transformed into Flora, goddess of flowers.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A pseudo-scientific belief that the hidden medicinal proper-ties or ‘virtues’ of a plant reveal themselves by the physical appear- ance of the plant; ‘the doctrine of signatures proclaimed that the Almighty … gave man a broad hint as to the use to which plants could be put. For example, those with heart-shaped fruit or bulbous roots were suitable for treatment of cardiac troubles …while scaly objects such as toothwort, pome- granate and pine-cones, relieved toothache’ (Blunt 141). This is of course nonsense. The names most closely associated with the theory are Theophrastus Bombast von hohenheim (!)

a.k.a parcelsus (d1541) and giambattista della porta (d1605) for his publication Phytognomonica or ‘plant indicators.’

Another late follower of the doctrine of signatures was Thomas Browne (d1682) who in his dis- course The Gardens of Cyrus identi- fies the Quincunx as a recurring geometrical arrangement that reveals a network of natural cor- respondences in nature. he glides easily from this to a the doctrine of signatures – that stones plants and roots and flowers contain encoded messages, analogies, symbols their properties uses and purpose (warner, 130).

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .